Understanding Presbyopia

How Does Presbyopia Happen?

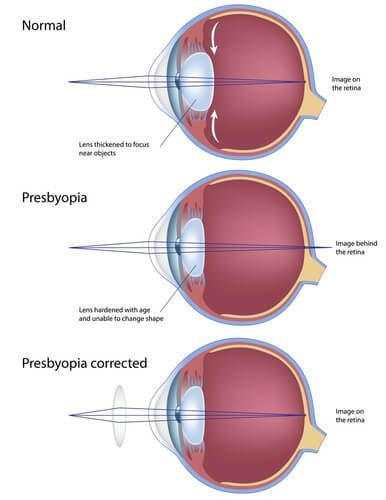

Presbyopia is a condition in which the ability to see up close in normal individuals, farsighted individuals, or individuals who have been nearsighted and undergone refractive eye surgery decreases as the age of 40 is approached. This physiological condition traditionally has required the use of eyeglasses with plus lenses or bifocals in order to read. Presbyopia causes the near point, the closest point from your eyes at which you can see objects distinctly, to recede as we grow older.

When we are young our near vision is very good. A child ten years of age can hold small objects or print two inches from his eyes and be able to see clearly. By age 30, the same individual would have to hold objects or print at least six inches away to see it clearly. By the time the individual reaches 40-45, it is no longer possible to see objects closely or to read comfortably at 12-16 inches. By their early 40s, most people have begun using reading glasses for such tasks such as sewing, or other hobbies requiring close vision, close work, and reading.

Nearsightedness Vs. Farsightedness

Farsighted individuals, who can see better at distance than at near without glasses, find that the loss of accommodation becomes apparent at an even younger age. This is because a farsighted person has to accommodate to see clearly at distance. When he tries to focus at near he has to throw in even more accommodation. Because farsighted individuals have a greater demand or need for accommodation, and the ability of the eye to accommodate decreases with age, we find that these individuals experience presbyopia at a much earlier age.

In contrast, nearsighted individuals can see better at near than at distance without glasses. These individuals can often wait longer before they need reading glasses. This is because the eye is normally in focus at near. However, if a nearsighted person wears glasses or contacts to correct their vision at distance then they will notice the loss of accommodation or presbyopia and often it begins for these individuals in their mid-40s. If there is enough nearsightedness (or myopia) then the nearsighted individuals may never need reading glasses because he can simply take off his glasses in order to read. However, such individuals must wear glasses at all times for distance tasks such as driving. Individuals who were nearsighted but underwent a refractive vision correction procedure will find their accommodative requirements would be the same as individuals who never wore glasses because the eye has already been corrected for distance and the nearsightedness eliminated.

For those individuals who grew up wearing glasses, by the time they reach 40 not only will they need glasses for distance, but often spectacles will be required for near vision. (This is the reason that Benjamin Franklin invented bifocals in 1760!) Bifocal lenses contain both a distance correction (on top) and a near correction (through the bottom). Therefore, it is possible with bifocals to see well at both near and distance by either looking through the bottom or top of the glasses. Other special types of glasses are often required for individuals who have to see at intermediate distances between near and distance. Such individuals may require trifocals, which have three segments in them depending upon the distance that one intends to look at. Such multipurpose eyeglasses have made it easier for many individuals by eliminating the need to constantly change glasses for different activities.

Reading Vision Over the Years

For over 150 years, the progressive decrease in accommodation with aging was thought to be a loss of lens flexibility often referred to as lens sclerosis. This theory was developed by the German scientist Helmholtz in 1855 and has been accepted as true until 1994. According to Helmholtz’s theory, when an individual focused his eye for near his ciliary muscle in the eye contracted and released the tension on the lens ligaments allowing the lens to thicken.

However, this theory was proved wrong in 1994 by an American scientist and ophthalmologist, Dr. Ronald Schachar who holds both a Ph.D. in physics and a doctor of medicine degree. Thanks to Dr. Schachar the errors in the Helmholtz theory were exposed and new applications found to reverse the loss of accommodation in the human eye. Dr. Schachar found that contrary to Helmholtz’s theory there was no relaxation of the lens principal (equatorial) ligaments when accommodation occurred. Schachar showed that the equatorial fibers of the ciliary muscles pull directly on the ends of the lens and cause it to thicken, thus allowing one to see more closely.

In fact, Schachar also found that the aging lens does not lose its elasticity due to sclerosis. The ability to accommodate is inherent even in an older eye. The principal problem appeared to be the growth of the eye with time. The human lens is like a tree and lays down new layers as we age. Thus the lens lengthens approximately 20 microns per year as we age. By the time we reach the age of 40 the lens has increased sufficiently in size so that the ciliary muscles are no longer taut in the eye and can no longer exert tension through the equatorial fibers of the lens when the ciliary muscle contracts for accommodation. For this reason, we lose our ability to accommodate at approximately the age of 40 and experience progressive loss of near vision as we get even older.